John Crater Still Missing but Novel Tracks Him Down

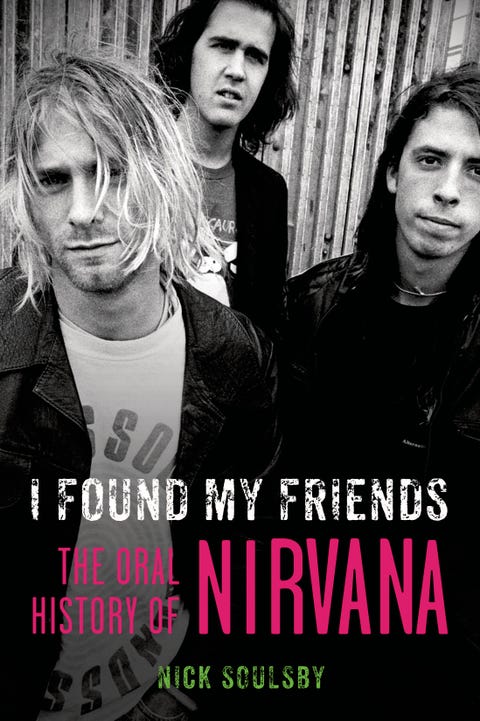

Nick Soulsby's new book, I Found My Friends: The Oral History of Nirvana, out March 31, tracks the history of the band through the words of friends and fellow musicians in the Washington state grunge scene of the 1990s. Illuminating and painful, this last chapter, exclusively appearing on Esquire.com, focuses on the torment and confusion surrounding what would turn out to be the tragic end of Kurt Cobain's short life and the band he left behind.—The Editors

One More Solo? The Curtain Falls

February to April 1994

The January session was to be the last time Nirvana worked together in studio. While there was only the scantest evidence of artistic activity from Cobain—he was too busy switching homes again—Grohl and Novoselic still presented compositions for Cobain's perusal as potential material for Nirvana. Even now—as late as January 30, 1994—no one could see that the end to Nirvana was within touching distance. The future was vague, but not preordained. There was no forewarning of the spiraling events that led to Cobain's death.

ADAM KASPER [producer, engineer]: I was struck by Grohl's songs and the demos we made that week. At the time I offhandedly made the remark that he should do a solo album someday . . . There was talk of the guys wanting a chance to include some of their songs on the new album work. Cobain listened to a few tracks and it seemed he was open to considering other material, but not much time or energy was spent on this.

STEVE DIGGLE [Buzzcocks guitarist]: I sat with Dave at the end of the tour and said, "We're gonna miss you guys, y'know?" because we got on really well on the road—all in [it] together. We were sat at the table and he said he had some songs he wanted to do when he got back. I have to be honest, I thought, I bet they're pretty good but . . . the drummer? You're not sure what he's got but...

Having spent part of 1993 on a reunion tour with Scream, Grohl joined other musicians in early 1994 for the soundtrack to the film Backbeat.

DON FLEMING [Velvet Monkeys frontman]: Thurston [Moore] put the lineup together and told Don Was we would do it but only if we could do it without any rehearsal and if we could do it in two days. That helped everyone with their busy schedules; we literally flew out there, learned the songs on the spot one-by-one . . . There are certain drummers, especially from producing, I've worked out are such a key element of the band. They can take a band that are great and make them a step above—that's what [Dave] did with Nirvana. There were great songs, great front man; the drums took it a step up, and that's why they were so successful . . . He brought so much energy to the songs and never fucked up. I don't remember about where they were at as the band at that point. They'd become very popular but I don't remember him talking about it at all. I think he was just there to have a good time.

While Cobain was increasingly absent as a creative artist, Nirvana as a performing entity rolled on and arrived in Cascais, Portugal, in February to play their first European shows since 1992. Cobain, Novoselic, Grohl, and Pat Smear had performed these songs so many times that whatever was occurring behind the scenes, their well-drilled onstage chemistry was still there.

STEVE DIGGLE: I remember those shows, standing at the side of the stage, hearing Dave Grohl's drums and just thinking, Jesus! It's like John Bonham! This guy can play! Krist was an amazing bass player and Kurt was sometimes quiet but suddenly this roar of a vocal and this intensity. Pat Smear—great guy and great guitarist, he blended in well. It was amazing to see, I'd heard the records but I was blown away by the live thing . . . I'd heard Bleach and I'd heard the Nevermind album, but the first time I saw their show I thought, Wow, I've got it now. Watching Dave Grohl just a few yards away banging the fuck out the drums, Krist to one side, Kurt in the middle belting it up, the intensity rocketing up and down . . . I saw what it was all about. Kurt was a great guitarist in his idiosyncratic way—using your limitations. A lot of people in punk are like that; it's not like you're some virtuoso muso guy, you never got that sense off him, but it was just the right thing—right on the button. It's the noise, the inflections. I was a big fan of Neil Young and the way he works the noise as well as the notes—that's passion, feeling, a lot of artistry.

Cobain's band mates had long since developed immunity to the roller coaster of his moods. For years he swung between spells of shyness, sullenness, or whatever.

STEVE DIGGLE: He was up and down on the tour—one day he'd be quiet, other times he'd be animated. Everyone gets like that on tours—you didn't detect anything heavy. There's a bit of video somewhere: I'm walking to the stage, he walks out [of] his dressing room and walks with me all the way to the stage—together. He was such a lovely guy, like they all were. All of them had learned something from punk rock and he'd taken it into this era—and he was true to it. There's a lot of inspiring things about the heaviness of what he was saying. They weren't there to be fucking bought. I thought he was sticking to his beliefs—heavy-duty, real things. Maybe dark and intense but real—we couldn't see where it was ending. As well as Kurt, Dave, Krist—incredible musicians and very thoughtful. Krist is very thoughtful! A big part of that band . . . There's the serious side, the intensity—I did get that from the way the band played. It was like thunder coming—but just in the dressing rooms, we knew about this, that we all deal with our own stuff when out on the road. But we did connect in a lot of ways with those guys. I could sympathize with that awkwardness.

Likewise, the drugs had been an issue for over three years now. There was only so long anyone could worry or cushion someone from their own actions. Plus the reality was that Cobain may have been unwell but he wasn't completely wrecked. One kind soul was sweet enough to share their own drug experience—quite a contrast to Cobain's private indulgence, which included a cushion of cash, professional minders, and a regular supply.

ANONYMOUS: We got into heroin and started making daily trips up to Seattle to go get it to keep from getting sick. That lasted for a couple years and then [we] . . . moved to New York . . . thinking we would get clean there. So, we got an apartment in Hell's Kitchen and found that, Wow! There's drugs on every street corner! It's fucking Christmas! So, you can see where that went. It took until 1995 before I got clean and ended up back in Olympia again. Yep, my parents kidnapped me from New York at the age of twenty-seven; humbling, isn't it? I was pissed, so I showed them and moved back to New York on my own and used for a couple more years, until I ended up temporarily blind from shooting up heroin traced with rat poison. Next thing I knew I woke up in a hospital and they transferred me to the medical rehab portion for a few weeks. Then I decided I didn't want to live anymore and kept threatening to kill myself, so they transferred me to the Beth Israel psych ward for a month. From there, a friend and my parents chipped in and paid for my rehab in Washington State, so I went directly there from New York. Let's see . . . That was my tenth detox and third rehab and hopefully my last.

Regardless of his physical condition, the In Utero tour had commenced in Europe as scheduled on February 4 with a TV appearance in Paris. The band returned to the city two weeks later with Cobain ducking out to visit an old friend.

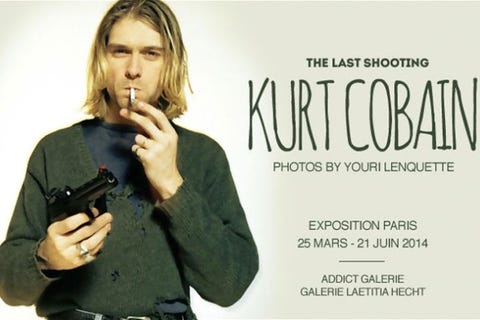

YOURI LENQUETTE [photographer, friend]: Kurt often came by my place and he'd spend the afternoon playing the guitar or just sitting on the sofa not saying a word, just being there. Then one afternoon he said, "Youri, I'd like to do a photo session with the band tonight, would you like that? Around seven or eight?" I was like, "Well, Kurt, are you sure?" I didn't really believe it, but he was positive—I had to ask him because he hated photo sessions. More often than not, rather than me using our relationship to get more out of him, he'd use the fact we had a friendship to avoid them! My assistant was meant to be off work that evening and I told him, "Go, they're not going to come. He says he is but he's not going to come." I didn't have a makeup artist either because she asked me straight, "Do you think it'll happen?" When I said no she confirmed she was heading off; she had something else to do that night. I went back home about eight thirty, had dinner, a bit later I got the call telling me, "We're coming in twenty minutes." They arrived around ten.

"The thing of holding the gun, playing with it—[Kurt] brought it with him and it was his idea."

It wasn't the best time for a photo shoot; Cobain's face was pockmarked and damaged.

YOURI LENQUETTE: He ended up wearing a lot of makeup because he had things on his skin as a result of his bad health and his bad habits. I told him straight, "It's going to look really bad." He agreed but I had to tell him I didn't have any makeup in the studio. My girlfriend happened to be a mixed-race girl, so he asked, "Can she lend it to me?" So he went into the makeup room, started putting it on without an assistant and, after a while, I go in. He's looking like Al Jolson! My girlfriend's skin was a light chocolate color; he has all this makeup made for her skin tone all over his face. I had to say it: "Come on Kurt, it looks ridiculous, we can't use it." So, I'm thinking this photo session isn't going to happen; it's late, I've got no assistant, we've got no makeup. I'm thinking it's best not to do it. Then this guy, who is always avoiding photo sessions even when there was a good reason to have one, he insists, "Don't you have someone you know who would have some white-skin makeup?" So I remember one friend who was OK to come out even though it was eleven now, [and I said] "Come right now, bring your girlfriend and her makeup." We just waited for him to arrive. Kurt did the makeup himself and it's all over the place but it was his idea and basically this whole session was happening because he wanted it. I wasn't commissioned by anyone except, I'd say, by Kurt himself. I wasn't ready to do such an important session—I didn't even have the films I liked to use; I just had to use others I had in the fridge from another shoot. The whole business was done with whatever we had. Artistically it wasn't my best session even if, looking back, it was the most important session of my career.

Unfortunately, Cobain does resemble a doll in some of the photos.

During this break in Paris, Cobain's well-honed sense of the pointedly mischievous was on display.

STEVE DIGGLE: He had a gun at the French gig—was pointing it out the window at the journalists. I was up in the dressing room thinking, What's he doing? Didn't know if it was a plastic gun or a real gun, to be honest. There was a whole bunch of stairs up to the dressing room at the Zenith—I'd been meeting some friends of mine so I'm milling around where the journalists were and I looked up and thought, Fuck, he's got a gun up there! He was pointing down at them. I headed upstairs and he was kneeling down by the window. I enjoyed that—it was great, funny.

YOURI LENQUETTE: The thing of holding the gun, playing with it—he brought it with him and it was his idea. Eventually I said, "OK, Kurt, let's do something else other than the gun." He's all like, "OK! So let's try this, oh, and what if I put this hat like this?" I had this ceremonial hat made with ostrich feathers I bought in Zimbabwe and he's trying it on. The others were waiting at the back of the photo studio until it was time do some of the whole band together. First it was just three of them because Pat Smear arrived a bit later. We finished around two in the morning, chilled a bit, drank a bit, he saw photos I'd shot in Cambodia in the temples of Angkor—he loved the place. So I said, "Look, Kurt, if you're so tired, if you're so fed up with everybody, just have a break. If you like that place I can take you there, we'll relax, I'll shoot a few photos of you so that'll cover expenses and you'll get to spend two weeks in someplace really different . . ." He was really into it: "How can we get the visas in the US?" Talking, talking, "Yeah, I'll call you to organize it when I'm back in the US." Maybe his last words were "Let's get organized for the Cambodia trip, great! Wow . . ." I took them down to their taxi and that was the last time I saw him . . . In 1994 everyone could see he wasn't happy. Some things still made him really happy—like having a baby, finding good music that sparked him—but I would still say he wasn't in the best mental shape. In all areas of life—whether his role as a rock star, his relationship with the band, his drug problems—this was not a happy spell he was enduring. He told me openly, "I'm fed up with everything." Looking at my photos of the Angkor Wat temple—remember, this was the early '90s and there were no tourists, you'd maybe see a bus or an adventurous Australian tourist . . . maybe a few monks but no tourists, nothing—he really liked the place and the fact it was deserted attracted him. He really thought that nobody liked him and that everyone was against him. He was deep into this very negative way of thinking. Plus there were the drugs. I told him to take a break, "You're huge, take a holiday. You can go away a few months, a few weeks at least—break out of this and when you've recovered you can come back fresh." That's where the Cambodia idea came in.

"[Kurt] really thought that nobody liked him and that everyone was against him."

Even at this late date, Cobain still spoke of new ideas he might try, whether it was escapes like Cambodia or new techniques he might add to his music.

STEVE DIGGLE: We spent a lot of time walking 'round these big arenas, me and him, and a lot of time on that bus. He told me he really loved the vocal of "Harmony in my Head"—I told him I smoked twenty cigarettes before I sang that to get the roughness in the voice. I said the reason I did that was that I read John Lennon did it before he did "Twist and Shout." Kurt loved that—said he'd try it out himself; he wanted that gravelly voice. He said that was his favorite song by the Buzzcocks. He was very down-to-earth, a bit of a fan, but we were fans of what he was doing. We went from there. We went through a lot of things like that—he asked me how we survived when we were locked in the tour buses. He said that in the vans from the early days you developed a sense of humor. I told him, "Sense of humor? Listen Kurt, coming from Manchester you grow up with it!" But it does help in those intense atmospheres . . . We also spoke about that shark that Damien Hirst did; he liked that—mentioned it to me, he seemed very favorable toward it. I was thinking, How does he know about that? I didn't think he'd be mentioning something like that—I thought we'd be talking about Neil Young more or stuff like that . . . There was one day we were all staying in the same hotel, waiting for the tour bus, Kurt said, "I wanna go with you guys." His tour manager said, "No, Kurt, we've got to do this an' that—you've got to come with us." He was insisting he wanted to come with us. That was nice—his heart was in the right place but he had a lot of interviews to do so didn't come with us in the end. It was a very natural thing with us, all of them, we'd hang out—no awkward moments. But we'd be walking 'round the stadium and there'd be fifty people chasing after him saying he had to do things—he'd say, "Steve, I just wanna walk here with you." I got what he was saying . . . Ironically we spoke about guns and stuff like that—not knowing what was to come. Now I put that together with him asking me how we survived and it feels like a profile of what was to come, something building up. But the great thing is we spent all that tour with Nirvana and I liked the record but I was turned on a lot more by them live.

The warm moments rarely lasted; the band was existing in well-catered tedium.

STEVE DIGGLE: You've got to remember, big gigs meant hours of hanging around. They had a couple of acoustics in the dressing rooms but that was it. The thing about those stadium gigs is you get a lot of traffic, so you've got to get there a bit earlier. You don't want to be hanging around too long—I like the spontaneity of turning up still feeling fresh, having a drink then getting on a stage—not hanging around for hours in a dressing room staring at the walls . . . Plus a lot of traveling involved—it wears you down, gets to you. I don't even know how many sound checks they did . . . Plus there was all this food and people coming up asking if you wanted to order your meal for after the gig. We went to look at the food for the rider before the show—fucking hell, there was everything! Meal upon meal upon meal—then they're asking us what we want for dinner! A table the length of a street you could help yourself to all day. On that tour you had to watch yourself—you could just eat all afternoon! Must have put on a couple of pounds on that one! People coming 'round saying they had to take down my meal for afterward but there's already everything there we could want. It's par for the course because it's also for the road crew—there's a lot of staff—twenty, fifty guys—a lot of people working so needing that food there. You can't just pop to the shops—not in a stadium. At the front there's a big car park, at the back there's a big car park full of tour buses—a lot of people working on those tours.

By March 1, the mood of the tour was at a perilous low as Nirvana strolled through virtually the same ninety-minute sets they'd played every night for sixty shows over five months and Cobain complained of illness—"bored and old" indeed.

YOURI LENQUETTE: There was some kind of destructive logic in him at the time. He believed the people around him didn't like him—which totally wasn't the case! From being on tour with Nirvana, seeing how they acted with him, they were really good people . . . The fact that he couldn't connect to these people anymore was a sign of depression . . . I have good memories of that session—I didn't feel there was any tension. It was just friends having drinks and shooting photos. It wasn't tense. But with depression you feel good some moments, then the very next day you're back to a negative way of thinking—it's not all one or the other. He didn't hate them, it wasn't a conflict, but my impression was he was brooding on this idea that nobody loved him, building up something not based in reality. It was just him; his whole way of seeing things was very dark . . . He didn't look well, he was in bad health mainly fueled by the use of drugs.

The tour crossed into Italy and up-and-coming Sicilian favorites Flor de Mal joined the tour.

MARCELLO CUNSOLO [Flor de Mal]: We were already huge fans of Nirvana . . . I had read all about him, about Kurt, I knew almost everything that was known at the time . . . It turned out Nirvana really appreciated our music, so my recollection is that the most beautiful thing for me was to stand in the same place as Kurt would onstage and to hear them live at such close range, playing just a couple of feet away from me . . .

It's a telling point. Cobain had become a media entity. In the early days the band had played to crowds of fellow musicians, often to clusters of friends. Fame had dragged Cobain into the spotlight, isolating him (partly through his own choices) while making him ever more real in the minds of complete strangers—he'd become a modern-day ghost.

MARCELLO CUNSOLO: All I remember is that once I saw Kurt, I could see a great malaise in his eyes. A darkness . . . Kurt didn't seem very good and to see it with my own eyes, it was very sad . . . The lineup commenced with the Melvins opening, then after that we played. Flor de Mal were the solo opening act for the concert in Modena because the Melvins noted that Flor de Mal were more appreciated than they had been. The audience wanted more and so we continued until Nirvana came on . . . During our sound check, Krist and Dave of Nirvana were behind the stage and danced (I even have a record of their dancing on video somewhere) . . . I remember that Kurt was always standing aside, aloof and usually stood with his eyes closed. The rest of the band would be together and were joking with each other, as I told you, during our sound check they were there with us all the time dancing to our music . . . After the sound check, I went to look for Kurt to give him a bottle of Sicilian wine. He was in the hallway outside, that's where I found him, behind the stage standing against the wall as if he was going to puke. He still took the bottle and took the time to say "thank you" and to bow to me kindly.

YOURI LENQUETTE: Like most people who take drugs, at some point they lie to you because they know what you're going to say . . . It was obvious, I could see what was going on, I had proof of what was going on, but it was difficult to have a real discussion because he'd never tell me the reality of things. In 1994 he lied about having an addiction when, at that time, he really was addicted . . . You couldn't have a real discussion, though—he really was in denial. It's hard dealing with people when they just don't want to tell you. If I asked him he didn't even try to deny it but it was always the same: "Yeah, well, but just these last three days." He would tell you he was doing good in some sense even when you knew that wasn't the case—it's a key symptom in a way, someone trying to tell you not to worry and that they know what they're doing.

As Cobain's last weeks disintegrated, only fleeting contacts remained.

YOURI LENQUETTE: He called me once from Germany—Munich—early one morning, maybe nine o'clock. He said he wasn't feeling good there and asked me if I wanted to come join them on the tour. I had to say no, I was really busy, I told him I couldn't just up and go to Germany. It showed me things were getting worse while he was there. That last phone call was very brief, I heard no more news from him. After that I just got it like everybody else, Rome, then that final news.

LISA SMITH [Dickless]: The last time I saw him he was trying to get in my apartment building to see if Courtney was at Eric Erlandson's apartment. I went downstairs to let him in the building—he looked like shit. Apparently they were having one of their many tiffs.

ERIC ERLANDSON [Hole]: It seemed like he wanted to play with other people and just have fun. No pressure. I believe he was working on ideas for something, who knows what, but he was not really in the head space to accomplish much of anything at that point.

PAUL LEARY [Butthole Surfers]: Shorty before Kurt's death, Gibby [Haynes] called me from rehab and told me that Kurt had checked in and was assigned to be Gibby's roommate. Kurt refused to be his roommate, and declared he wanted to escape over the back wall. Gibby told him that all he needed to do was walk out the front door, but Kurt insisted on going over the wall.

"Krist told me, 'John, don't believe anything you hear right now. Kurt is fine.'"

That was Friday, April 1. Mazzy Star—one of Cobain's favorite acts—played Seattle's Moore Theater. Cobain didn't make it, but Krist Novoselic did.

JOHN PURKEY [Machine]: I ran into Krist at the show and with all the bad news going around I asked him straight whether it was all true. He just told me, "John, don't believe anything you hear right now. Kurt is fine." Krist seemed like he honestly felt like Kurt was fine.

It was Tuesday, April 5; just nine weeks had passed since Cobain had stepped off the plane in Europe.

YOURI LENQUETTE: I was trying to call him because he'd said this Cambodia thing with enough certainty that I thought I needed to know yes or no because I couldn't put a two week trip to Cambodia in the middle of my schedule without organizing. I was trying to call his home, he gave me a number, his home number, I called . . . There was no answer. I told my girlfriend, "Look, I don't know what's going on with this Cambodia trip with Kurt, I can't speak to him . . ." She called me on the Friday night to tell me, "You've got your answer if he's going to come or not. The news just broke. He was found dead at his house . . ."

PAUL LEARY: Dark days that I do not miss . . . I remember the day I heard on the news that Kurt had died. I was with [musician] Daniel Johnston* in the living room of his parents' house watching the news. When it was announced, I said, "Oh my God." Daniel's mother asked who that was, and Daniel said, "That's the guy who wore my [hi, how are you] T-shirt."

STEVE DIGGLE: We were brothers for those weeks. When I got back and saw the news that he was gone—I couldn't believe it. You don't expect it. Seeing him on the TV all I could think is he was still alive, that it was just days ago I'd seen him.

The long-form video that emerged under the sneering title Live! Tonight! Sold Out! was the final project executed under Cobain's guidance.

KEVIN KERSLAKE [music video director]: The team that finished the film was the same team that started it . . . With a lot of the videos that I did with Nirvana, you could say that stream of consciousness played a role . . . We wanted something that just washed over you rather than simply taking you on some sort of narrative ride. Even the stuff that we were going to shoot for it was supposed to have that sense that you were stuck in a bubble—but it wasn't supposed to just be the one bubble it ended up being. It was supposed to be a few different takes on the experience of being him, of being in the band . . . This was just the stuff that was under his bed, on his shelves and on the floor throughout the house. We hadn't yet gone on a big hunt for other footage that existed. We were just sort of forming the "base coat," if you will, for the movie that was going to be painted over with many different brushstrokes. It ended up being, to me personally, something that still feels just like a base layer . . . because the appearance and likeness rights hadn't yet been obtained for various people who were in certain shots or scenes—because those people couldn't be found or didn't want to be in the movie—we ended up cutting a lot.

Nothing was left but archival footage and latter-day sainthood.

Cobain's death was not just a Hollywood spectacular, a morality tale of rise and fall. A high school dropout from an isolated corner of the United States had, less than eight years after leaving Aberdeen, connected with people the world over. His death was all the more powerful because he died as one of the rare souls to win fame and great fortune only to declare celebrity to be null and void; something to despise and to leave behind.

YOURI LENQUETTE: What I think of is not Kurt as the big rock star. It's just Kurt, this really young guy I knew, this very talented young kid, who lost his life and all the promise he had.

Grief at his death bonded his band mates, his family, and his friends with teenagers and fans in every country of the world. This was a man, however, who had little beyond disdain for what came with the spotlight—he would have been dismayed to learn that death itself served to elevate him even further above his community. In a book about that community, it seems only right to remember the many who were lost alongside him.

DAVID YAMMER: Many friends, colleagues, and acquaintances have passed away in the last twenty some-odd years . . . What I do like to dwell on is the many more people from the scene who survived, straightened up a bit, or even kicked real danger out of their lives altogether. I am very proud of my scene. We were family and still are: Northside punx rule!!

GLEN LOGAN: Faces of folks no longer with us come to mind. These thoughts make me smile a bit, then a wave of loss follows. It makes me once again appreciate the human side of all this. To many, grunge is a big musical movement or genre. To me it is more about the diverse and incredible folks that sought an emotional outlet in the form of the music they created and the lifestyle they lived. Some of these folks didn't make it through but they are not forgotten, even the ones who may not be the big names that many outside Seattle have come to know.

There are sadnesses scattered throughout the bands interviewed in this work. Kai Davidson of the Joyriders also took his own life:

MURDO MACLEOD [Joyriders]: [Kai] was a good example in most things. Hardworking, compassionate, funny, wild, very smart, very loving, and an enthusiast . . . That's been my experience of people in bands over a long time—those are the sort of people they are, in general, and I'm friends with many of them to this day. They've enriched my life. They enrich everyone's life.

Colin Allin of Skin Barn was shot dead while being robbed for his laptop in Nicaragua; Sean McDonnell of Surgery sank into a coma after an asthmatic attack.

JOHN LEAMY [Surgery]: [Sean] was one of the funniest, driest guys, who could also wash up real nice and meet your parents and charm the pants off of them. And then he would write a song about some unmentionable whore or something. I miss that fucker.

Jeff Wood of Forgotten Apostles was taken by brain cancer; Scott F. Eakin of Knife Dance, brother of Tom Dark, died of a heart attack at age thirty-eight, while drummer David N. Araca was taken by a brain aneurysm at twenty-six; Ian McKinnon of Lush overdosed in 1990.

SLIM MOON: We all still miss [Ian]; he was a really cool funny guy—very, very popular in Olympia.

Drugs killed Rich Rosemus and Dale Moore of Oily Bloodmen; Slater Awn of Lonely Moans died a month prior to Kurt Cobain's demise.

J. M. DOBIE: Slater's attraction to heroin was similar to Kurt's in that he also suffered from a great deal of physical pain—he was fixing a friend's car and got crushed underneath it. When his doctor suddenly cut off his prescription pain meds, he turned to street drugs to numb his pain.

This book serves as a celebration of Nirvana, but it is as much about the many musicians who made the underground into the home that the superstars never wished to leave. This book is a tribute to what was created and to the people who are still making it what it is.

PAUL KIMBALL: There are so few artists of any sort that you can talk about a time pre- and post- and have it be meaningful. Nirvana was one, and they were just some guys up that street at one point. That someone from our midst went on to make this massive global and cultural impact is a crazy thing, but it's not the thing. It felt, at times, after Nirvana reached the levels they did, like the rest of us from the Olympia music scene were standing next to a massive explosion that shook everything around us, took some of us out, launched some of us to new places, and then re-formed the landscape completely afterward. But after the noise recedes and the smoke clears, you look at the smoldering crater for a while, scratch your head, and then go about your business.

--

From I Found My Friends by Nick Soulsby. Copyright © 2015 by the author and reprinted by permission of Thomas Dunne Books, an imprint of St. Martin's Press, LLC.

*Correction: This article originally misidentified Daniel Johnston as the founder of K Records. He is a musician. We regret the error.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

John Crater Still Missing but Novel Tracks Him Down

Source: https://www.esquire.com/entertainment/books/a33510/nirvana-kurt-cobain-book-excerpt-i-found-my-friends/